In Park County, Mont., North Fork of Horse Creek Road with a “No Forest Service Access” sign.

Photographer: THOMAS PRIOR FOR BLOOMBERG BUSINESSWEEK

This Land Is No Longer Your Land

The fight

over preserving public land during the Trump era is taking a strange,

angry twist in Montana’s Crazy Mountains. Both sides are armed.

Brad Wilson is following a forest

trail and scanning the dusky spaces between the fir trees for signs of

movement. The black handle of a .44 Magnum juts prominently from his

pack. If he stumbles on a startled bear at close range, the retired

sheriff’s deputy wants to know the gun is within quick reach, in case

something stronger than pepper spray is needed. Wilson isn’t the type

who likes to take chances; he’s the type who plans ahead.

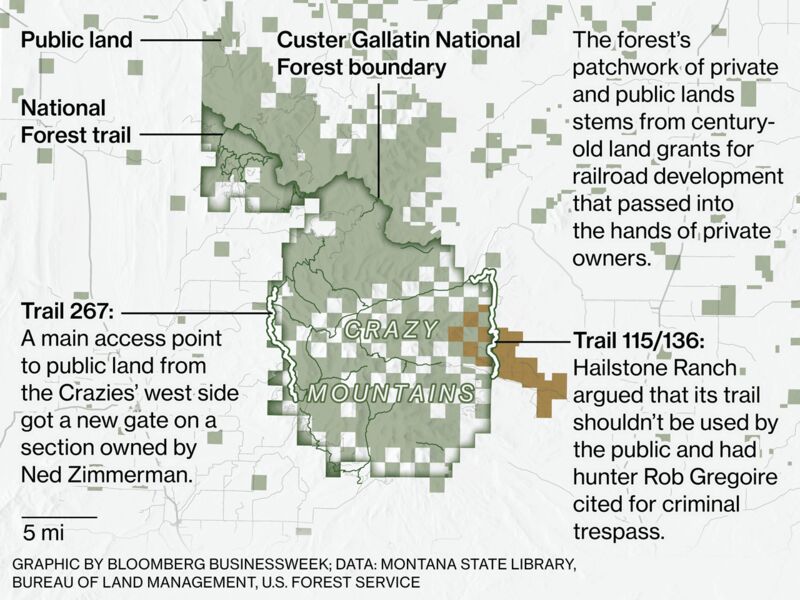

Before setting foot on this path, he unfolded a huge U.S. Forest Service

map and reviewed the route, Trail 267. He put a finger at the

trailhead, which was next to a ranger’s station, then traced its

meandering path into the Crazy Mountains, a chain in south-central

Montana that’s part of the northern Rockies. Like many of the trails and

roads that lead into U.S. Forest Service land, Trail 267 twists in and

out of private properties. These sorts of paths have been used as access

points for decades, but “No Trespassing” signs are popping up on them

with increasing frequency, along with visitors’ logs in which hikers,

hunters, and Forest Service workers are instructed to sign their names,

tacitly acknowledging that the trail is private and that permission for

its use was granted at the private landowners’ discretion.

Retired lawman Wilson says ranchers have become more obstacles than neighbors.

Photographer: Thomas Prior for Bloomberg Businessweek

Wilson, 63, is out on the trail to show me how the paths weave through private plots before reaching a destination he loves, and to show me why he loves it: The pebbled trout streams are crystalline, the elk run rampant, and painterly snowcaps break the big sky. The ranches along the way are pretty great, too, the kind of real estate that inspires—and, if acquired, perhaps even satisfies—the hunger a lot of people feel for scenic refuge. Many of the landholders are newcomers from out of state, though some old-timers remain—families that earned their deeds generations ago, the principal paid by ancestors who shivered through pitiless winters in tar-paper shacks. Wilson has been hiking and hunting the Crazies since he was a little kid, but only in the past year or so, he says, have the private ranchers seemed more like obstacles than neighbors. “They could shut down pretty much the whole interior of the Crazy Mountains, as far as I can see,” he says.

He trudges up a rooty slope and, after a blind bend, sees something straddling the trail that stops him cold. It’s a padlocked metal gate. He hiked this trail a couple of weeks before, and the fence wasn’t there. A sign on it reads, “Private Property: No Forest Service Access, No Trespassing.” It’s exactly the kind of sign he’d been bad-mouthing a few minutes earlier, but he wasn’t expecting to see one here. The locked gate feels like an escalation, a new weapon in an improvised war.

A debate is taking place across the country over preserving land for recreational public use, but most of the attention is focused on vast swaths of historically or scientifically significant terrain that Presidents Barack Obama, Bill Clinton, and to a lesser extent George W. Bush protected under the national monument designation—for example, Bears Ears in Utah and Katahdin Woods and Waters in Maine. These disputed trails leading into the Crazy Mountains represent another front in the escalating battle over control of federal territory, and the fighting here is just as contentious as over the monuments. Historic settlement patterns in the American West created a checkerboard pattern of landownership: Public properties are often broken-up plots, resulting in numerous access disputes. According to a 2013 study by the Center for Western Priorities, that dynamic has effectively locked the public out of about 4 million acres of land in Western states; almost half of that blocked public land, or about 2 million acres, is in Montana, according to the study. The push to end public thoroughfare is either an overdue reassertion of private property rights or an openly cynical land snatch, depending which side of the gate you’re standing on.

Before Wilson turns around and walks back to the trailhead, he vows that he’ll be better prepared next time. Alongside the .44 he’ll pack a pair of super-heavy-duty bolt cutters, and he swears he’ll tear that gate down.

Late

last October, in the dying days of the Obama era, a U.S. district judge

issued a verdict that seemed to set a precedent for paths like this

one. The Texas-based owners of a Montana property called Wonder Ranch,

about 100 miles southeast of the Crazy Mountains, had sued the Forest Service

after the government filed a statement of interest claiming an

easement—a legal agreement to use a portion of someone’s land for a

specific purpose—on a trail that ran across the ranch’s property before

reaching the Lee Metcalf Wilderness. The Forest Service said the trail

had been routinely used as an access route to the forest by the

government and the public for decades, and therefore it should be

considered public because of historical use. The owners’ suit argued

that the government had no right to an easement. The Department of

Justice countersued, producing evidence dating back more than a century

showing that the public and the government consistently used the trail

for packhorses and hike-ins. The Forest Service won the case.

Had

the landowners been able to show that the trail had been used for at

least five consecutive years only by those who’d received their

permission, their claims of private control might have held. That helps

explain why Alex Sienkiewicz, the forest ranger overseeing the district

that includes the Crazy Mountains, every year sends an email to his

staff reminding them never to ask landowners’ permission to use trails

that the government already considers public. “By asking permission,” he

wrote in last year’s reminder, “one undermines the public access rights

and plays into their lawyers’ trap of establishing a history of

permissive access.” That didn’t mean anyone could veer off the trail and

slip onto the private property—that’s trespassing, no question about

it—it just meant the trail itself should be considered a public

throughway.

A disputed road leading to public land, blocked by the landowning Galt family, who sell self-guided hunts on their ranch.

Photographer: Thomas Prior for Bloomberg Businessweek

Public land advocates smelled a contradiction, since the new president was positioning himself elsewhere as a champion of private property rights. And regardless of what he said, Trump’s campaign had tapped into a very deep well of antigovernment sentiment, the sort that Nevada rancher Cliven Bundy appealed to when he occupied public territories and led armed standoffs against federal agents in 2014 and again in 2016. The co-chair of a state group called Veterans for Trump pleaded guilty to helping organize the ad hoc rebel militia, and Roger Stone, a longtime Trump adviser, has been one of Bundy’s most vocal supporters. Immediately after the election, whether or not the results had anything to do with their actions, the Crazy Mountains landowners launched a collective blitz to take control of the trails leading to Forest Service property.

Rob Gregoire, an engineer from Bozeman,

Mont., says he had little idea what awaited him when he marched up the

Crazy Mountains on Nov. 23, 2016. He’d been granted a state tag allowing

him to hunt bull elk on the eastern slopes, and before he set out for

Forest Service land, he’d called Sienkiewicz, the district ranger, to

double-check that the public trail marked on his map was indeed public.

The ranger had explained agency policy to him, which indicated that the

trail was public, but told Gregoire to use his own judgment if a

landowner objected.

Gregoire decided to go for it. When the trail

veered through a private plot called the Hailstone Ranch, he spotted a

No Trespassing sign that read, “The Forest Service Has No Easement

Here.” He ignored it, consulting his GPS to make sure he never strayed

from the path onto the private ranch land. The landowner somehow

detected that he was using the trail (“I think he had an alarm or

something,” Gregoire later speculated) and called a sheriff’s deputy,

who was waiting for Gregoire to return at the end of the day. The deputy

charged him with criminal trespassing.Shortly after that, the owners of nine ranches neighboring the Hailstone went after Sienkiewicz. Back on July 20, a volunteer at Public Land/Water Access Association Inc., a Montana nonprofit that supports open public access to federal lands and waterways, had gotten hold of, then posted on its Facebook page, Sienkiewicz’s most recent annual email reminder to his staff advising them never to sign visitor logs for trail access or ask permission. The property owners apparently assumed that Sienkiewicz had posted the item himself—proof that he was behaving as a political activist, not a public servant. The ranch owners sent a letter to U.S. Senator Steve Daines, a Republican representing Montana, saying in part, “As a direct result of this inflammatory Facebook post, we have many questions about the FS position regarding access across our private property.” Several of the ranchers who signed the letter have also been listed as contributors to Daines’s political campaigns in the past five years.

In May, Daines echoed the landowners’ complaints—and forwarded a screen shot of the Facebook post—in a letter to Thomas Tidwell, then the chief of the Forest Service, and to Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue, whose agency oversees the Forest Service. Less than two weeks later, Representative Pete Sessions (R-Texas) got involved, firing off a similar complaint to Perdue and Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke, who has a long history in Montana. An avid hunter and fisherman, he was born in Bozeman, about 40 miles from the Crazies. He was also a Montana congressman, filling the seat Daines had occupied before he moved to the Senate. (At least one of the ranchers donated to Zinke’s campaign.)

A road leading toward the Crazy Mountains.

Photographer: Thomas Prior for Bloomberg Businessweek

It’s not known if Perdue or Zinke took direct action after receiving the complaints (Perdue’s, Zinke’s, and Sessions’ offices didn’t return calls for this story, nor did Hudson’s attorney). But the week after Sessions’ letter was sent, Sienkiewicz was removed from his job as district ranger, pending an internal review, and moved to a desk job evaluating gold mining proposals in another part of Montana. The public controversy surrounding his suspension stretched on for more than four months and brought significant local criticism to the Forest Service. “Alex was just following the Forest Service manual,” says Bernard Lea, who spent 36 years in the Forest Service in Montana before retiring and becoming a leader of the Public Land/Water Access Association. The day before Sienkiewicz was told of his transfer, Gregoire agreed to settle his trespassing charge and pay a $500 fine. The county attorney overseeing the case happened to be the husband of one of the landowners who’d signed the letter to Perdue and Daines complaining about Sienkiewicz. “With him on board,” Gregoire says, “I didn’t think I could win.”

Defenders of Sienkiewicz and Gregoire—a group that included land access advocates, proprietors of recreation businesses, wildlife groups, and individuals—cast the developments as evidence of an under-the-table assault on public lands that the Trump administration appeared to endorse, if not initiate. This spring, Trump requested that Zinke’s Department of the Interior review national monuments, designated or enlarged since 1996, and possibly downsize them, a step he said could rectify what he considered a “massive federal land grab.” Several politicians from Utah, such as Orrin Hatch, Rob Bishop, and Jason Chaffetz, had led the downsizing push, and for years they’d been advocating turning such lands over to the states—the strategy Trump had earlier declared would result in a selloff to the highest bidder. The department eventually suggested downsizing six of the 27 monuments under review, but the ultimate fate of those lands and waters remains in limbo; the matter will go to Congress, and the conservationists have said they will fight the new boundaries in court.

PERC’s Anderson says ranch owners serve nature better than government can.

Photographer: Thomas Prior for Bloomberg Businessweek

“I absolutely hate the movie A River Runs Through It,” says Terry Anderson,

senior fellow and the former president and executive director of the

Bozeman-based Property and Environment Research Center, commonly known

as PERC.

“It destroyed fly-fishing in Montana.” He’s referring to the wave of

tourists in fresh-off-the-rack waders inspired by Brad Pitt in the film,

who’s guided through life in leaf-filtered light by fraternal love and

river sport. Anderson grew up in Montana, and he remembers when the

Bozeman airport terminal was smaller than a coffee shop, and you could

spend all day on a hike without seeing another soul. The unofficial

state motto is “The Last Best Place,” and the feeling that untrammeled

natural landscapes are becoming scarce has engendered a strain of

possessiveness. At a gas station near the Crazy Mountains, you’ll find

T-shirts that say “Montana Sucks—Now Go Home and Tell All Your Friends”

and bumper stickers that read “Montana Is Full—I Hear North Dakota Is

Nice.”

Anderson has carved out a field for himself in something

called free-market environmentalism. Along with his job at PERC, he’s a

professor emeritus at Montana State University and a senior fellow at

Stanford’s Hoover Institution, a libertarian-leaning think tank. In

op-eds published across the country, he’s an evangelist for limited

government and private property rights. He views many environmentalists

with undisguised contempt, and they generally return the favor.Like many nonprofits, PERC doesn’t disclose its funding sources, but Greenpeace International has posted records showing that they’ve included Exxon Mobil Corp. and the industrialists Charles and David Koch. Anderson probably wouldn’t worry too much about how that looks: He believes the private sector, in most cases, is a better steward of nature than the government.

At the right place and the right time, the notion that the Crazies are being overrun by hordes of weekenders desperate for recreation is easy to conjure. It’s best done on a sun-shot Saturday morning in summer, close to Half Moon Campground, which is near the lone uncontested public entry point on the east side of the Crazies. Here, campers and hikers gather before dispersing into the relative solitude of the vast mountain wilderness. On one such morning in August, no fewer than 33 vehicles overfilled a parking area near the trailhead. “It’s like a Walmart parking lot,” grumbled Dario Quilici, a 35-year-old who was hiking in with Gino Mussolini, his German wirehaired pointer, for some camping and fishing.

Quilici’s plan was seat-of-the-pants. He thought he might spend three or four days hiking to an exit point on the far side of the mountains, but he didn’t realize that the most direct trail was blocked by the gate Wilson had confronted. Other possible paths were also contested. When I told him this, he redirected his criticism away from the parking lot and toward the landowners. “I bet they have some lobbying power,” he said. “They just want to keep everything like it’s their own private reserve.”

The town of Wilsall, at the foot of the Crazies.

Photographer: Thomas Prior for Bloomberg Businessweek

“In the places where now there are signs,” Anderson predicts, “you’ll see a locked gate.” His comment is an informed one. He counts several of the landowners involved in the Crazy Mountains disputes as friends, including the owners of the Rein Anchor Outfitting and Ranch, who operate a hunting lodge and signed the letter against Sienkiewicz. PERC’s affiliation with politically connected outfitters that stand to profit if trails are closed bolsters the sense, to Wilson and others confronting locked gates, that a void in coherent policy about public land management is being filled by cronyism that rewards wealth and connections above all else. Another co-owner of the Wonder Ranch, Frank-Paul King, a friend and former student of Anderson’s, served on PERC’s board. Hudson, the man who got Representative Sessions involved, is King’s brother-in-law, and he’s also a board member and the former president of the Dallas Safari Club, a group that made national headlines in 2014 when it auctioned off a trip to Africa to hunt an endangered rhinoceros. (The winning bidder, who paid $350,000, traveled to Namibia and shot a black rhino bull, an animal the club said had threatened the rest of the herd.) The Dallas Safari Club has granted PERC funding for, among other things, a study on “private conservation in the public interest.”

In 2016 the Dallas Safari Club hosted a fundraiser featuring the big-game hunting enthusiast Donald Trump Jr. that netted $60,000 in campaign donations to the Republican National Committee. “The candidate’s family connection to hunting and its legacy gives DSC a huge opportunity to have the right people in place as advocates for our mission,” the club’s newsletter stated. After Trump was elected, Hudson was listed as an organizer for a post-inaugural fundraiser called “Opening Day 45,” which featured Eric and Donald Trump Jr. as co-chairs. It was canceled after TMZ published an early draft of the invitation last December, promising personal access to President Trump, along with a multiday hunting excursion with his sons, to anyone who donated more than $500,000, sparking criticism that the sons planned to peddle access to their father.

This circle of big-game hunters is relatively small, which means links among them are numerous enough to allow critics of the Trump administration to claim political malfeasance, and they’re tangential enough that defenders can argue that they’re coincidental and easily misconstrued. One person who has hunted with Trump Jr. is Senator Daines, of the anti-Sienkiewicz letters. The two men met last fall in a camp in Montana during an elk hunt. Daines later called on Trump Jr. to return to the state to campaign on behalf of Greg Gianforte, who was running for the congressional seat Zinke gave up to lead the Interior Department. This spring, Trump Jr. explained that he had grown to trust Daines unequivocally; when the senator told the president’s son that Gianforte was “an awesome guy,” he decided to get involved. “That vouching was enough for me,” Trump Jr. said at a rally in April.

On a Thursday evening in August, a couple

dozen people gathered in an old schoolhouse in Livingston, Mont., to

grill Mary Erickson, the Forest Service’s supervisor of the Custer Gallatin National Forest,

about Sienkiewicz’s reassignment. Most of the people in the crowd

viewed the case with skepticism or outrage, and Erickson appeared to be

choosing her words carefully to avoid pushing anyone toward the angrier

end of the scale.

The trail access issue was extremely sensitive

inside the Forest Service, she explained, and potentially costly, too.

The Trump administration was proposing

a 73 percent cut in the Forest Service’s capital improvement and

maintenance budget and an 84 percent reduction, from $77 million to $12

million, in its trail program budget. The Wonder Ranch case, she

observed, had cost the government “in the millions of dollars,” and it

wasn’t over yet—the landowners were appealing the decision, and it now

sat with an appellate judge. “I’m not saying we’re never going to go to

court, but the Forest Service is going to be careful about when we go to

court and make sure we’re going to court on cases we can win,” she

said.

A padlock on a gate blocking access to the Porcupine Lowline Trail.

Photographer: Thomas Prior for Bloomberg Businessweek

That notion didn’t sit well with some in the audience, particularly those who believed that if the unfolding drama showed bias toward an interest group, it was toward the private landowners. Nick Gevock, the conservation director of the Montana Wildlife Federation, told Erickson that Sienkiewicz was a public servant and he’d simply taken the side of the general public.

The agency in mid-October announced it was giving Sienkiewicz his job back. But Gevock’s frustrations spoke to an unresolved question underlying all of the disputes: Who, exactly, is the Forest Service supposed to serve? On the agency’s website, former Director Thomas Tidwell wrote that its guiding principles were clearly established by Gifford Pinchot, the service’s founding chief, during the Gilded Age—“a time when the nation’s resources were being exploited for the benefit of the wealthy few,” Tidwell stated. “The national forests were based on a notion that was just the opposite—that these lands belong to everyone.”

The public access advocates say they’re not sure they trust the spirit of Pinchot’s original message has survived intact. The mixed signals coming from the Trump administration mean everything rests on how those sometimes conflicting messages are interpreted. Zinke has repeatedly insisted, without offering specifics, that he is pro-access, and on his first day in office he pledged to fight against the “dramatic decreases in access to public lands across the board” that he said were plaguing America. “It worries me to think about hunting and fishing becoming activities for the landowning elite,” he said.

But this past July, while public land advocates were protesting the Interior Department’s pending move to downsize the national monuments and hikers were cursing the new No Trespassing signs in the Crazies, Zinke traveled to Denver to speak at the annual conference of the American Legislative Exchange Council, or ALEC. The group, a conservative lobbying coalition that helps lawmakers draft legislative proposals, has energetically pushed for the potential transfer of federal lands to the states. Whether Zinke’s speech clarified the government’s general, overarching philosophy on public-vs.-private control of lands that are currently federal, only members of the lobbying group can say for sure. Unlike several other speeches delivered at the conference, Zinke’s wasn’t transcribed or published, and it was closed to the general public.

(A

previous version of this story ascribed a grant from the Dallas Safari

Club to PERC that was for The Conservation Fund. The text has been

corrected in the 28th paragraph to reflect the accurate study.)

Infected

animals live just over the border on three sides of the state in

Wyoming, the Dakotas, Saskatchewan, and Alberta. In 2016, a deer tested

positive north of Cody, Wyoming, just eight miles from the Montana

border. “The odds are good it’s

already here. We just haven’t discovered it yet,” says John Vore,

FWP Game Management Bureau chief.

Infected

animals live just over the border on three sides of the state in

Wyoming, the Dakotas, Saskatchewan, and Alberta. In 2016, a deer tested

positive north of Cody, Wyoming, just eight miles from the Montana

border. “The odds are good it’s

already here. We just haven’t discovered it yet,” says John Vore,

FWP Game Management Bureau chief.